Patent Law is Not Like Zen Buddhism

| Cross-posted to LinkedIn. |

Probably the most important principle in patent law is that a claim for a new invention is not patentable even though no prior art teaches every feature in the claim, so long as multiple prior art references can be combined to arrive at the claimed invention. In this case, the invention is said to be “obvious.” (At least in the United Sates; for my European friends, the invention would found “lack inventive step.”) There is an additional requirement, though, that is often missed by examiners (although they do pay lip service to it) and that is that the prior art as whole must have led a person having ordinary skill in the art to arrive at the claimed invention. In the context of patent prosecution, the burden is on the Patent Office to articulate a rationale as to why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have arrived at the claimed invention.

This point is illustrated by a case I recently ran across in my personal archive. The patent was ultimately granted in 2001 to General Electric and describes a method of weatherproofing electric busways. These are conductors of powerful electric currents between, for example, factory buildings in an industrial complex. The invention involved pouring flowable polyurethane sealant over the plastic housing so that the sealant flows into the cracks in the housing to completely seal the busway. Prior approaches involved using a caulking material which was prone to human error in terms of obtaining a complete seal.

This point is illustrated by a case I recently ran across in my personal archive. The patent was ultimately granted in 2001 to General Electric and describes a method of weatherproofing electric busways. These are conductors of powerful electric currents between, for example, factory buildings in an industrial complex. The invention involved pouring flowable polyurethane sealant over the plastic housing so that the sealant flows into the cracks in the housing to completely seal the busway. Prior approaches involved using a caulking material which was prone to human error in terms of obtaining a complete seal.

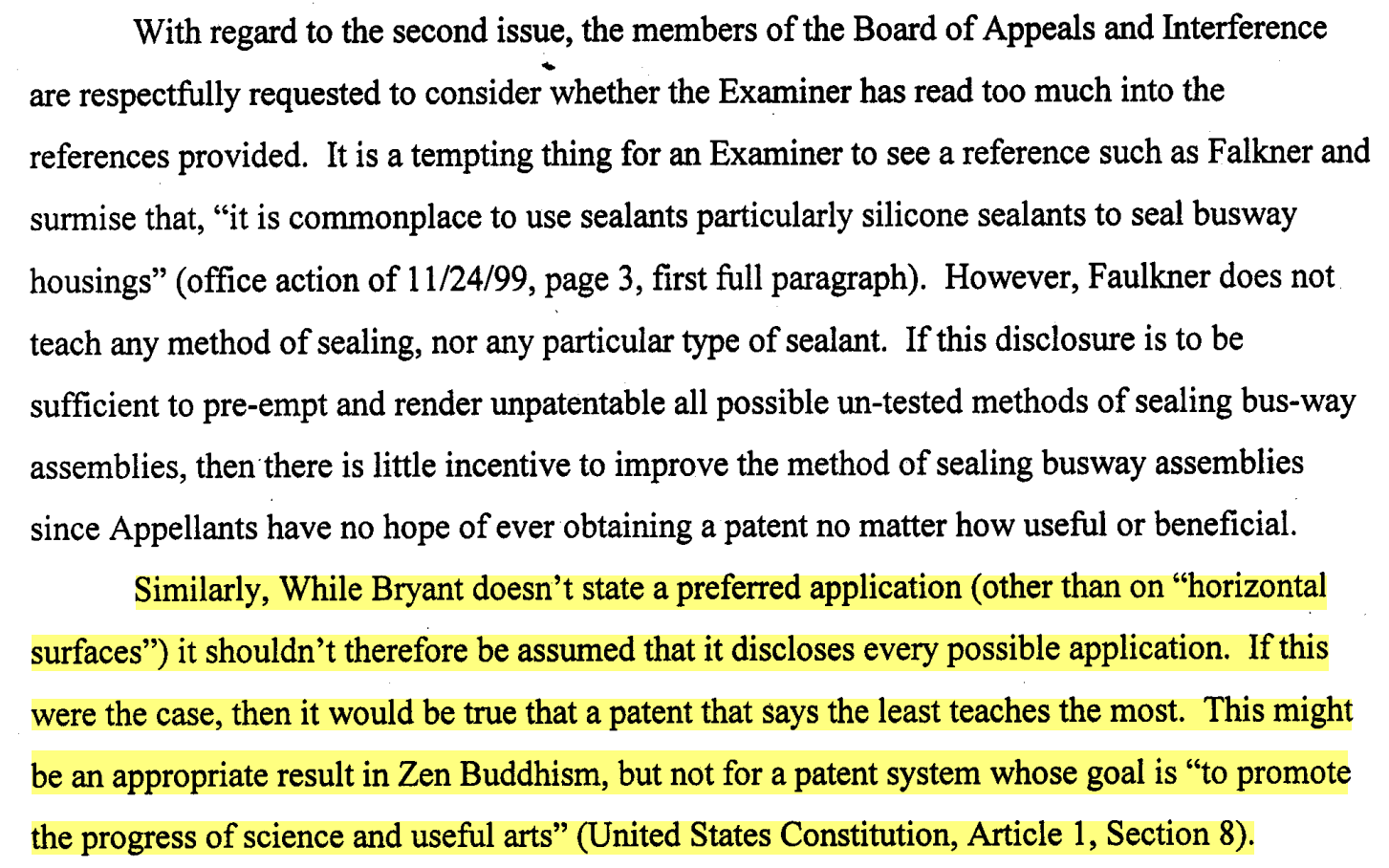

In the last rejection the examiner cited three references. teaching (1) a busway housing (“Faulkner”), (2) sealing “busbar corners” using a caulking material (“Slicer”), and (3) a flowable sealant (“Bryant”). It's also worth noting that all Bryant says about the usefulness of his flowable sealant is that it can be poured onto “horizontal surfaces.” Clearly, he had all the ingredients necessary satisfying all the claim limitations – at least individually. However, he couldn't explain how a person skilled in the art, faced with this art, would have arrived at the invention.

In the Appeal Brief that I drafted, here is how I articulated this weakness in the Examiner's rejection:

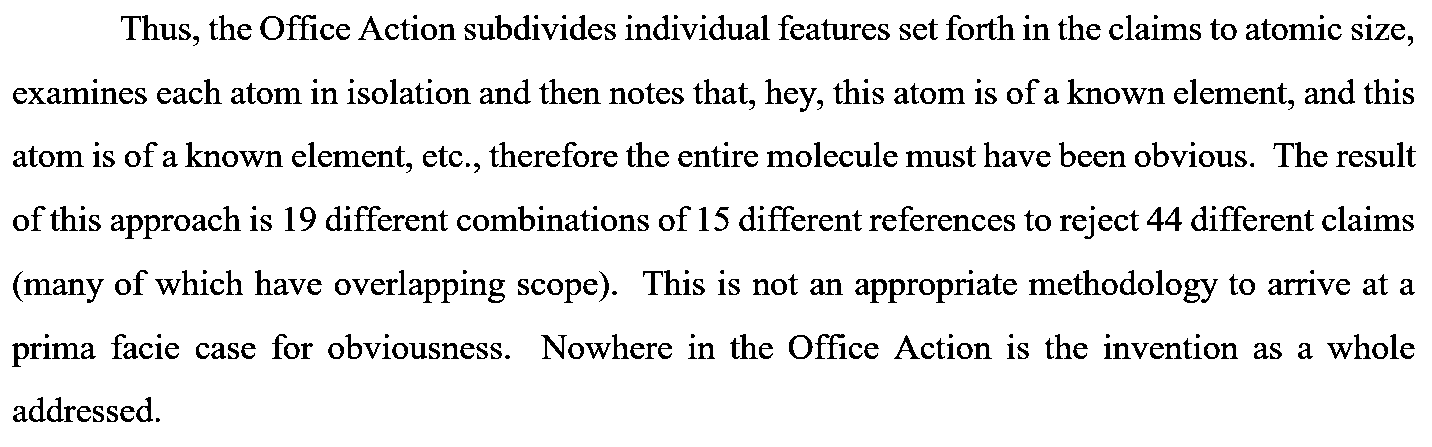

I had an even more extreme example while working at VMware. The invention in this case was an algorithm for device to passively determine the subnet of its attached computer network. (Never mind if that is mostly gibberish to you.) The Office Action was 25 pages long and contained 19 different combinations of 15 different references in order to meet all the limitations of the claim. The examiner in this case did not even make an attempt at articulating a rationale for combining the references in a way that would cause a person skilled in the art to arrive at the claimed invention. Here is how I articulated this in my argument:

The patent was granted in 2011 after these arguments were digested. Perhaps a call to the examiner's supervisor helped.

The bottom line is that it is not enough to simply determine if the individual features of an invention were known in separate prior art references. What matters is whether there existed, at the time the application was filed, a basis in the prior art for the skilled artisan to have arrived at the claimed invention.

Discussion